Designing for Impact (Without a Mandate)

With Shift Cycling Culture’s 2026 Barcamp happening this week, I’ve been thinking back to the topic I brought to the 2024 event. Primarily because the then localised example that I had in mind when writing the piece has since evolved into our day-to-day lives whether that be protectionist politics, dilution of sustainable legislation or a continued retraction of the green premium…

Shift Cycling Culture’s 2024 Barcamp at Canyon’s HQ in Koblenz, Germany

The point I was trying to make back then was simple, and slightly uncomfortable: design engineers and product designers have a responsibility to act on climate change mitigation throughout the design process, even when they’re working for brands where net positive practice is not part of the company’s values or DNA.

That’s easily said but much harder to do.

Low demand tends to mean low budgets. Low budgets mean limited freedom or scope for exploration. Before you know it, the responsibility can quickly be sidelined into a nice-to-have theory rather than a mission-critical practical inclusion.

This is where the challenge actually sits.

What follows isn’t a framework or a manifesto. It’s a set of prompts that I’ve found useful when you’re trying to reduce climate impact from inside projects/brands/clients/organisations that don’t consider it a key driver, and where influence, time and money are all limited as result.

1. Gain first-hand knowledge of your materials

Understanding the materials going into your products is foundational. Not just what the data sheet says, but what the material really is, how it’s processed, the repercussions of its consumption, and why it was specified in the first place.

The more direct your knowledge is, the easier it becomes to spot lazy assumptions and inconvenient truths. This kind of understanding builds slowly, but it compounds.

2. Focus on metrics that matter to both impact and the business

Some metrics quietly influence a lot of decisions at once. These are the ones worth paying attention to.

Mass is a good example. It feeds into footprint calculations, but it also affects unit cost, vehicle battery range, perceived performance and value, and logistics fees. When you work with metrics like this, sustainability stops being a separate conversation and instead can become a silent beneficiary.

3. Use fast, low-cost tools early

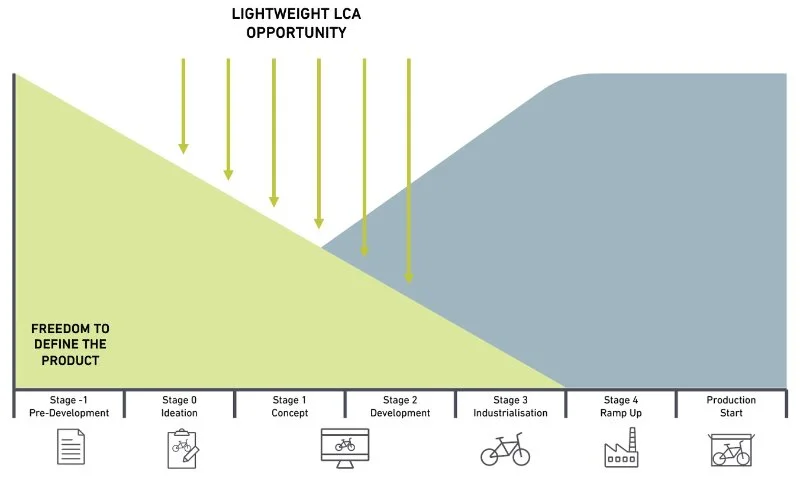

Waiting for perfect data can be lethal for climate action in product development. Don’t let perfect get in the way of good!

Free or low-cost tools, such as TU Delft’s IDEMAT Eco-Cost tool, make it possible to compare options early in the design process, when change is still cheap and easy to initiate without arduous stakeholder engagement and consultation.

The resolution isn’t great, and the accuracy is limited, but directionally useful information early on is far more valuable than precise numbers once everything is fixed. Leave it too late and it’ll just be an extensive and accurate report on the opportunities that passed you by…

4. Question tests, load cases and industry ‘learnings’

A lot of test regimes and load cases were defined during periods of material abundance. They’re often inherited without much scrutiny, even when the context they were created in has radically shifted.

Asking why a requirement exists, and what would actually fail if it were relaxed, can reveal space for innovation that otherwise stays hidden.

To be clear, this isn’t making the case for not testing! Far from it. Instead, its asking you to dig a little deeper in understanding why you’re testing something and what that test is intended to replicate.

For example, when was the last time that you saw an ISO fatigue test that gave any useful indicator on how that cycle count correlated to an intended service life for a product?

5. Experiment with topology optimisation

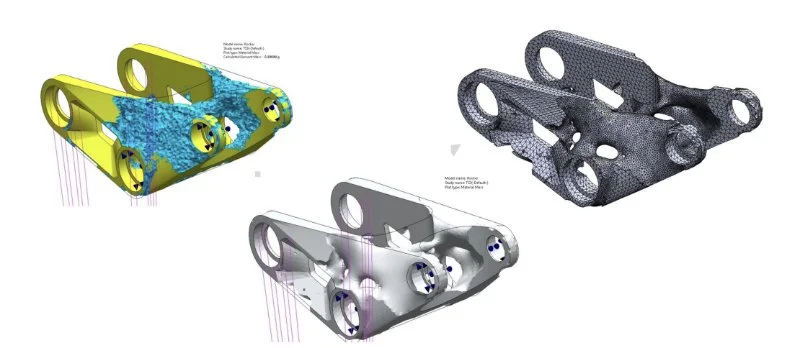

Once you have a clearer picture of real loads, topology optimisation becomes genuinely useful.

The tools are improving quickly. They’re easier to use, often built directly into CAD environments, and increasingly viable for real components with smart features such as tooling direction constraints. Used with intent, they could significantly reduce material consumption without undermining performance.

6. Maximise use and minimise decay

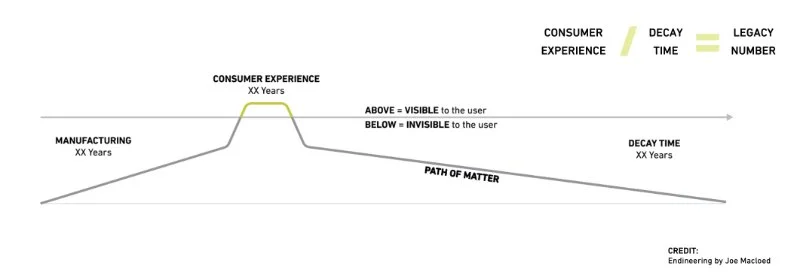

Impact isn’t only about how a product is made. It’s also about how long it remains meaningfully used.

Joe Macleod explains that extending the customer experience duration and shortening the decay period leads to a lower overall legacy number. This also means resisting the urge to over-specify. Materials should match the intended service life, not outlast it by decades without reason.

7. Design for genuine need and emotional attachment

Products that meet real needs and create some level of emotional attachment tend to be used longer, repaired more readily, and replaced later.

8. Avoid unnecessary churn

Minimising model year updates and resisting trends and fads reduces waste, complexity and pressure on supply chains. It can also improve trust, both internally and with customers.

9. Look for alternative value creation

Sustainability constraints can open up new revenue opportunities rather than close them off.

Circular models, subscriptions, take-back schemes and refurbishment programmes can address environmental impact while strengthening the business, provided they’re designed, funded and supported intentionally rather than bolted on.

10. Design for separation and material recovery

We have DFA (Design for Assembly) in our design processes, but where’s DFDA (Design for Dis-Assembly)?

Designing parts and interfaces for separability makes a tangible difference to end-of-life outcomes. It’s also a golden opportunity to build in post-sale repeat revenue opportunities through the support of service and repair if done well and integrated early enough.

11. Normalise the use of PCR materials

Post-consumer recycled (PCR) materials still carry a lot of perceived risk, often more than is justified.

Designers can help derisk their use through strategic part design, thoughtful component placement and honest internal conversations. Shifting the stigma around recycled content is as much a design-driven demand problem as it is a supply chain one.

Closing thoughts

None of this requires a sustainability-led brand or a bold corporate mandate. It mostly requires curiosity, technical judgement and a willingness to question things that have gone unchallenged for a long time.

Climate mitigation rarely arrives with a clear brief or a dedicated budget. More often, it shows up in small, everyday decisions that are easy to overlook.

The little day-to-day choices that you make matter! Choose what you do with them wisely…